Organizing my mp3 library has become my preferred form of procrastination. Instead of reading the news, I make sure each song is accurately labeled, and each album has the appropriate artwork. It's a soothing antidote to the buckshot lunacy of algorithms and feeds. The other day I noticed I have 2,062 songs by Muslimgauze. At first, I thought this was an error, but no, I've somehow collected 127 Muslimgauze albums over the past twenty years, and new records continue to appear each month, which is mighty prolific for a man who died in 1999.

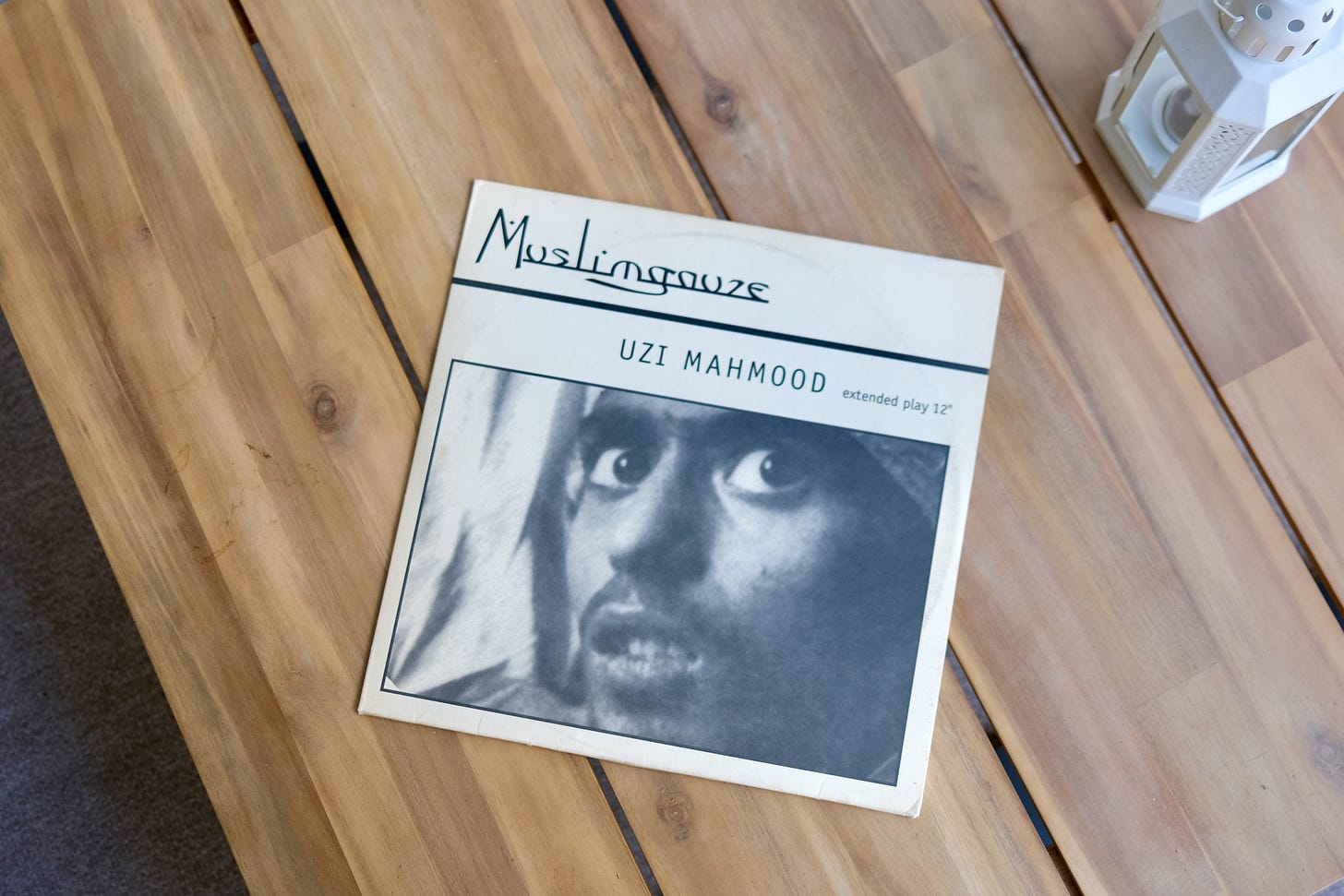

I heard my first Muslimgauze record in 1998 while deejaying the midnight hour at WCBN in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Rooting through the new releases one night, I found an album called Uzi Mahmood with a grainy image of a man's face on the sleeve. The camera caught him looking at something off to the left, and he looked afraid. There was no other information, but the onslaught of hyper-saturated drums and clipped Arabic vocals rearranged my sense of electronic music. I imagined this record as Palestine's answer to the faceless mythos of groups like Underground Resistance, Drexciya, and Basic Channel.

Years passed before I learned that Muslimgauze was the moniker of a white man named Bryn Jones, who lived a reclusive life in a Manchester suburb. He created the Muslimgauze alias in 1982 after reading about Israel's invasion of Lebanon. Then he devoted the remainder of his life to making albums with names like The Rape of Palestine, Vote Hezbollah, and United States of Islam—an odd move that feels like strip-mining another culture's trauma for experimental music. The singer and producer Lafawndah offers a different point of view: "It would be superficial to say that Bryn's art would be more legitimate if he'd spent time there—that perspective has turned contemporary art into a failed state of a different kind." Perhaps both viewpoints can coexist. Either way, I think Bryn Jones's frantic output points to something much heavier and weirder, something that remains just beyond the grasp of understanding.

Noting the "inconceivably deep sadness" that haunts Jones's music, the critic Ian Penman finds it hard to believe this melancholy came from a place he never knew. "The sadness seems much deeper and further ingrained than that, approaching pathological—almost as if the terrible dispossessed 'birthright' of the Palestinians corresponded, secretly, to some personal scar or shadow in Jones's own life." (These quotes are from The Quietus, which published several musicians' reflections on Jones's work, and it's the most substantial information I've encountered. I'm still trying to track down Ibrahim Khider's book, Chasing the Shadow of Bryn Jones, which is part of a handsome box set I cannot afford. Here’s a trailer from Cultures of Resistance Films.)

Although he was invited, Jones never visited Palestine. He hardly left his parents' home. He was thirty-seven years old when he died. But the records keep coming.

At least 202 Muslimgauze releases are circulating today: that's an album every month during his seventeen-year career, and he said he recorded a new album every week. Record labels could not keep up. Stop, they told him. We have too much. After Jones died, his parents told his label to take whatever they wanted. “I declined,” said Geert-Jan Hobijn, who runs Staalplaat. "Then they said they would put the rest in the dumpster, so I took as many masters as I could." I've been thinking about this image all summer: all that music stuffed into trash bags.

Two decades after his death, Jones remains a black box. They say he had little interest in religion. They say he was a zealot. They say he was apolitical. In the end, there's only the music. For such an elusive figure, his music is profoundly present. He was a talented drummer, but his production skills edge towards the otherworldly. His oversaturated drums beat inside your brain stem, hammering out rhythms that cast a freaky shadow across everyone else's narrow turf of industrial, hip hop, techno, electro, and dub. The field recordings and radio clips are astounding when you check the date: 1987, 1991, 1995. Where was he finding this material before the internet?

"There are no lyrics because that would be preaching," Jones said in a rare interview. "It is music. It is up to you to find out more. You can listen to only the music, or you can preoccupy yourself more with it." But how do you reckon with such an overwhelming catalog? My music widget says I have over 291 hours of Muslimgauze—nearly 13 solid days. And so the artist's obsession becomes the listener's obsession.

I think it's a worthwhile journey. If you're new to Muslimgauze, start with thirty seconds: "Jagannath, Jagannath Who?" from Jaab Ab Dullah. Then I'd suggest tracking down "Uzi Mahmood 7", a constellation of razor drums, crackle, and dub. These are the building blocks of the Muslimgauze universe. If that works for you, give the moodier heat shimmer of Mullah Said and Sandtrafikar a shot. (Some current artists have built careers out of attempting to reproduce these two records.) See also: "Veil of Tear Gas" and "A Small Intricate Box Which Contains Old Blue Opium Marzipan." Or consider Ryoji Ikeda's Remix #6, a low-slung engine of vision-blurring drums that decimates every other breakbeat to ashes. The remixes are where things get most interesting. Artists around the world continue to remix Muslimgauze, and, in the process, they are rewiring, reclaiming, and broadening his single-minded vision.

Jones's fanatical output haunts me because his reasons remain unintelligible. An album every week. I try to imagine the rhythm of his daily life. His relationship with his parents. Those trash bags. His devotion has produced a body of work that continues to regenerate beyond the grave. New Muslimgauze albums and remixes will probably keep appearing long after we're all dead, and it's a beautiful image: a feedback loop of remixes from every continent until there's just one great big endless drum.

Listening & Reading

All of the above reminded me of the sucker-punch thrill of hearing Ice Cube's "Jackin' for Beats" in 1990. (Here's some backstory.)

Or dig into something a little less fraught with Sasha Frere-Jones's mellow guide to krautrock and kosmische psychonauts.

As for the mechanics of listening to music, I'm grateful to Mario Villalobos for introducing me to Doppler, an elegant and dead simple MP3 player for the desktop and telephone that doesn't get tangled up in clouds, feeds, streams, or regional licensing bullshit. The price is beyond fair, and the guy who created it, Ed, is incredibly friendly and constantly working to improve it. Support Ed instead of Apple or Spotify.

"Although the classical 20th-century music snob still endures vestigially, the species peaked with Gen X before breathing its dying gasps through Elder Millennials and '00s hipsterdom." A solid argument via Kneeling Bus.

Finished all 1158 pages of Murakami's 1Q84. I've noticed I have two types of reading modes: the first is needful reading when I want to be entertained, edified, or enraged. Then there's open reading, when I give up any expectations and sometimes logic altogether, placing myself entirely in the author's hands. This type of reading is a rare gift, but there were some good long stretches in 1Q84, even if there's the uneasy sense that Murakami is trying to figure out his story while you're reading it. But then you hit a description like this: The rough waves of the Pacific. It was a thick, darkish sound, as if many souls were gathered, each whispering his story. They seemed to be seeking more souls to join them, seeking even more stories to be told. Or a character trying to resist the babble of his brain: I'm just a machine. A capable, patient, unfeeling machine. A machine that draws in new time through one end, then spits out old time from the other end. It exists in order to exist.

Some Interstate Scenes

Dehydrated. The desert’s silence was hell on my tinnitus.

A Matter of Degrees. Lose enough faith, and you might forget how to live.

Radioactivity. Scrolling down the dial in search of the midnight call-in shows, those carrier waves of national rumor and patchwork theory.

This was long. Thank you for reading.

Checking my own collection I only have 4 albums (Hamas Cinema Gaza Strip, Narcotic, Wish of the Flayed, and Re-Mixs 1) but have played them endlessly. But the joy is every time someone mentions Muslimgauze I get to discover a new album.

And as you said, amazing the amount of work he created (and lost).

I'm fond of the Veiled Sisters / Gun Aramaic era myself.