God Knows Where

They're like another species to me, these people who believe they know what's going on.

For eight years, I kept a nightly journal. Each night I would write a few hundred words that cataloged my regrets, dreams, and memories alongside the day's headlines and outrages. Last year, I made a fair chunk of this public. I believed this habit would help me keep track of my life, these notes for my future self. But it gradually became a journal of compulsion, an exercise in keeping a streak for 2,921 days. Strange, these blinkered rules I create: do something every day or not at all. So this year I'm giving up the nightly journal. Perhaps it’s more fruitful to think in scales of months rather than days; maybe this will help me avoid having my thoughts chewed up by the two-minute hates that each hour of online living seems to bring.

On the first day of the year, I stood before the humming pencil grids of an Agnes Martin canvas at the Columbus Museum of Art. The ancient Greeks believed God was a geometer, but I think she was closer to the mark: “Geometry has nothing to do with it,” said Martin. “It’s all about finding perfection, and perfection can’t be found in something as rigid as geometry. You have to find it elsewhere, in between the lines.” This seems like a good philosophy for an extreme season.

On the second day of the year, C. and I took down our Christmas tree while the television talked about the vandalized homes of Congress. A pig's head, misspelled demands, etc. It felt like an echo of the man who drove through Nashville on Christmas morning, playing Petula Clark’s “Downtown” before detonating himself. American violence was getting weirder, more dramatic flourishes for the people watching at home. Then came January 6. The scene was unthinkable yet oddly familiar: shaky footage of zealots in the thrall of a cult religion; desecration performed for cameraphones, the toppling of hallowed symbols, and the berserker's delight in smashing things. The Bush years were defined by an awful mantra: We will fight them over there. But now…

This was the last gasp, some said. No, it’s the start of something worse, said others. They're like another species to me, these people who believe they know what's going on and what will happen next.

Here in Ohio, downtown Columbus was boarded up several days before the inauguration. Plywood and yellow tape covered the capitol building, the courthouse, and the library—a windowless city of cops and joggers. As we walked along the river, a terse email arrived from the art museum "urging visitors to stay away from downtown in the interest of public safety. All ticket holders will be contacted with any payments automatically refunded." A few days later, pundits on cable news said the right-wing mobs "failed to appear." What happens when the hunger for spectacle goes unfulfilled?

Meanwhile, I still haven't absorbed the happy fact of our new president, whereas the shock of the last one remains clear. Maybe it's like getting punched in the face; the blow comes quickly, but the pain takes time to fade.

I'm still writing each night, focusing on fiction. Sometimes it feels like carving concrete with a fingernail, and I have to remind myself that if I’m not having fun, I’m taking myself too seriously; I’m certainly not writing for the money. But making up stories can feel like such a foolish errand when a chyron somewhere says Arizona man identified as horned, shirtless Capitol rioter. If faith in fiction is good for anything, maybe it’s the stock market.

I’m learning a new winter grammar of spike proteins and variants named after nations, sudden stratospheric warming and unbalanced polar vortexes, meme stocks and diamond hands. I scroll through a story about cryptocurrency investors who lost the passwords to their digital wallets. They stand in gardens and empty parking lots, looking pensive.

Everything feels true and false at the same time. Only now am I beginning to appreciate how much work it takes to keep my brains away from the buzzsaw of instant reactions and trending topics. And I'm failing. I worry about my sense of the world, my murky politics and little opinions, how they're probably programmed by algorithms coming from god only knows.

Maybe it's common knowledge now, but I just learned that Netflix has a thumbnail algorithm, some proprietary bit of robot-logic that tailors the promotional images for movies and television shows to each person's taste. This explains why my library is a bizarre collection of peculiar still-shots and peripheral actors. Will I be more likely to watch Casino Royale because there's a poster with Judi Dench talking on the telephone? Probably. But I have no idea what you're seeing; a helicopter with guns blazing, maybe, or a close-up of Daniel Craig's jaw.

Hopefully someday soon we'll have algorithm-free zones, spaces that are clearly labeled like a product without pesticides.

I’m thinking about my father's notebooks again. How he coped with grief by wandering through discount department stores, fixated on tracking down the correct size, exact model, or shade of color for something he thought he needed for his little apartment. Non-slip adhesives for the bathtub, the ones shaped like starfish. A particular brand of mechanical pencils, the ones with little white erasers. He always carried a small notepad in the back pocket of his khakis, and after he died, I found stacks of them, their pages jammed with his tiny scrawl: Lampshade repair. Talk to neighbor. Screen for bathroom faucet. Eggs are good for protein.

More and more, his notebooks feel like a balm against these digital winds, a climate ripe for faith dealers and dogma. He didn't understand how the world had become so interlinked, how its information could live on a screen. It felt like an optical illusion, a cheap bit of sleight-of-hand. Information was supposed to be earned through experience, through a combination of effort, luck, and scribbling into your notepad. Information required action, and my father craved the human contact needed to get it. The sales clerks would check their stock and make calls to other locations for a linen drum lampshade or a pair of loafers with tassels. He'd eventually find the item, but he would not purchase it, deciding he didn't need it after all.

Perhaps somewhat related to the above rumination on attention: I’m attempting to read Gustav Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony, his novelization of the saint’s struggle with vice and distraction while searching for salvation in the desert.

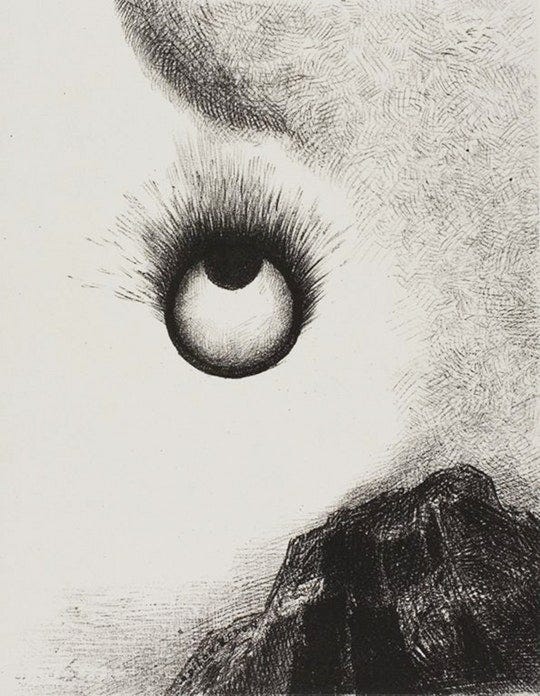

Flaubert’s account inspired one of my favorite artists, Odilon Redon, whose eerie etchings sought to capture the "unfettered, immaterial world of the psyche." The titles alone conjure worlds reminiscent of a Godspeed You! Black Emperor album: Then There Appears a Singular Being, Having the Head of a Man on the Body of a Fish, Everywhere Eyeballs Are Aflame, and Different Peoples Inhabit the Countries of the Ocean. (And now you can buy a Temptation of Saint Anthony face mask because we’ve built ourselves a fine little hell.)

Current hobby: Driving around Ohio at night, listening to Vatican Shadow.

Panthea Lee’s monthly essays have given me much to consider, and I admire her willingness to steer into the skid.

Eighty minutes of gorgeous fuzz and drone via Black Swan’s Repetition Hymns. Perfect winter music.

Light the Barricades, the series of electrified shrines that Candy Chang and I created in Los Angeles in 2019, is slated to be exhibited at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, next month—if plague conditions permit, etc. We also made a book about the project.

My most worthwhile purchase: a three-dollar screensaver of a Koi pond that I find tremendously relaxing. (I recommend the Night Water option.)